I like the idea, in this Instagram age of carefully curated self-promotion, of sports documentaries like “Southpaw – the Life and Legacy of Jim Abbott.”

It’s refreshing to see a film that’s come about without its subject asking for it; not that Abbott was exactly reluctant to participate in the project, he said. It’s just that, well, when he heard the idea, he figured his whole story had already been told.

But stories about his story? About Abbott’s lasting legacy, living on 26 years after he retired from Major League Baseball? Objectively, there was more there, things for even him to learn.

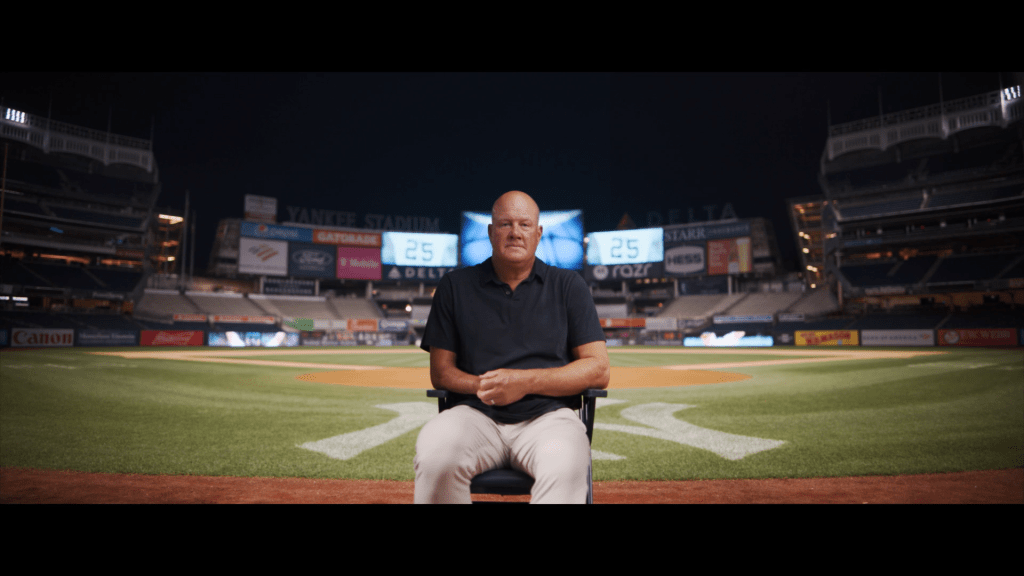

“I didn’t really realize how many people were watching and connecting to my play,” Abbott said by phone Tuesday, on his way to Yankee Stadium to deliver the ceremonial first pitch. “So to see that sort of play itself out, to have [the filmmakers] go and track some of these folks down and see their accounts was really touching. Really, really touching.

“You just don’t know who’s watching, you know?”

And no matter how well you think you know the story of this one-handed pitcher who starred for the Angels for several seasons, I hope you’ll be watching “Southpaw – the Life and Legacy of Jim Abbott” as it premieres on ESPN at 6 p.m. Sunday.

Even Angels fans who were there for the Abbott years, who remember the Michigan kid skipping the minor leagues and finishing third in Cy Young voting in 1991, should glean some new perspective from this retrospective about the nimble left-hander.

Won’t tip too much of the good stuff, but there’s a depth of feeling here that’s bigger even than the one-handed no-no that enticed producer-director Mike Farrell to pursue the project in the first place.

He frames the pitcher’s story around that no-hitter at the old Yankee Stadium on Sept. 4, 1993. Abbott, whom the Angels traded to New York, and his defense held a stacked Cleveland Indians lineup – Jim Thome, Manny Ramirez, Albert Belle, Kenny Lofton and Carlos Baerga – without a hit in a 4-0 victory.

But what really makes the moment, as former Yankees manager Buck Showalter said in the film, was that it felt like “a day when baseball and life repaid Jim for everything he had meant and the impact he had made on so many human beings.”

That’s the heart of Abbott’s story, and why his time in Anaheim was so important. Probably part of the reason he said he still feels most like an Angel.

“Through the years, they’ve been so kind to me – even though they traded me,” said Abbott, a longtime Newport Beach resident. “I still have such a connection and I think that shows through in the film. They were the first team that took a chance on me, and took a leap of faith to draft me and bring me up so early.”

It was also with the Angels that he learned to both bear and appreciate the burden of being Jim Abbott.

At the beginning, Abbott was, at times, reluctant to be a role model. In the documentary, Abbott explained: “I think of it as growing up, wanting to fit in, looking to success, playing sports as a way to get there, and then getting there and being set apart again.”

He thought people’s perception of him would change once he reached the big leagues, but of course the attention only increased. He was inundated with media requests, and often insulted by the media’s insinuations that he was, in some way, a gimmick. It could be a drag and a drain, and I imagine, a lot of pressure to perform – not only on the mound but as that capital-I Inspiration.

“I’d be up in the clubhouse where I always wanted to be with my teammates, playing cards or listening to music, and inevitably I’d get a pat on the back,” Abbott said in the documentary. “‘A team official would say, ‘Jim there’s somebody down by the clubhouse who’d like to meet you.’”

To his credit, the pitcher kept stepping up to the plate. A real angel, this guy, as limb-different children and their families came from all over, taking what were essentially pilgrimages to meet this big leaguer who was more than that, who was a real-life symbol of what was possible for them.

“In sports, there’s a lot of false hero worship,” Farrell said. “We automatically assign morality: ‘He’s a great person because he can shoot a basketball or put a hockey puck in the net.’ But Jim is who you hope he is; he’s actually that way – an incredible person. And I think I’m a better person for having gotten to know him.”

We hear how Abbott – who remains, Farrell learned, “a central icon in that [limb-different] community” – came to cherish those often-heavy meetings, how he reached the realization that there was no avoiding the fact that his major-league experience was just going to be different. And how that meant he could make impressions that transcended his sport.

That transcend the sport still, we learn in this documentary that’s so moved Abbott – despite those initial reservations.

The fortune cookie message here might be, what? Embrace what you’re reluctant to?

“To see what was so personal to me at the time, what it meant to other people, that is so gratifying and I’m so thankful for that,” Abbott said. “I hope people like it.”