It was great seeing former Orange County Rep. Chris Cox recently at a Pacific Research Institute event at the Pacific Club in Newport Beach. He gave a talk on his new book, “Woodrow Wilson: The Light Withdrawn,” of which I’m only going to review the portions on domestic policy. If you’re reading this on anything connected to the internet, thank Chris for his 1998 Internet Tax Freedom Act, made permanent in 2016. It prevents direct taxes by state and local governments on such things as email and usage bytes.

Not so averse to taxes was Wilson, who imposed the dreaded federal income tax in 1913 with the 16th Amendment. It started out at 7%, but Wilson soon raised it to 77% in 1918 to pay for World War I. Originally only a tax on rich people, Cox writes, “with annual inflation raging at 18%, millions of taxpayers were being pushed into higher tax brackets each year …. The elderly living on meager savings and the indigent were hardest hit.” Price controls squeezed farmers, who couldn’t raise prices to pay for the higher taxes.

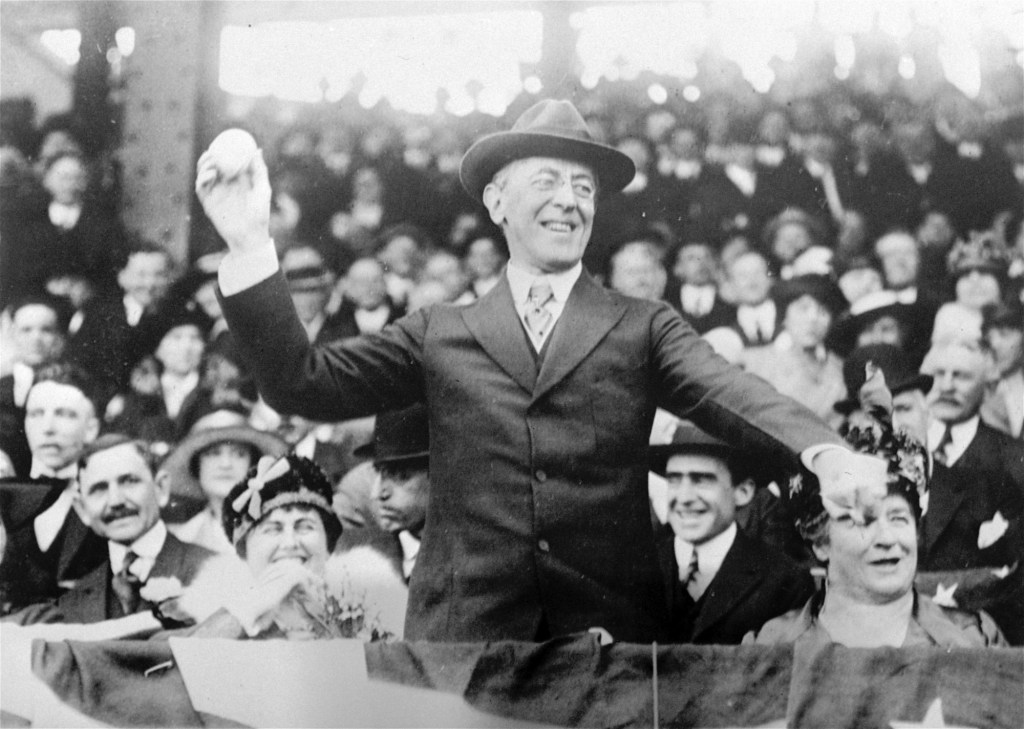

Wilson, Chris said in his talk, long has been considered part of the progressive movement that brought us not only the income tax, but in 1913 the Federal Reserve Board, in 1919 alcohol Prohibition with the 18th Amendment and in 1920 women’s suffrage with the 19th Amendment and throughout that time moves to improve conditions for Black Americans.

But on the last two, Cox said, Wilson was regressive. He made his mark in the northeast as a professor and president of Princeton University in New Jersey, then as governor of the Garden State. But he grew up in Virginia, Georgia and the Carolinas and, as president of Princeton, wrote “slavery was not so dark as painted.”

After Reconstruction ended with the Compromise of 1877, the South quickly re-segregated. And in 1913, when Wilson became president, Chris writes, “Jim Crow and the Democratic Party ruled every state government” in the South. But in the federal government, “For years, Black and white government employees had worked together in the same offices and at the same machines, desks and tables.”

Wilson changed that. At a cabinet meeting, Postmaster General Albert Burleson, the son of a Confederate Army major, pushed for resegregation not only in his department, but “in all departments of the government” as “best for the Negro.”

Navy Secretary Joseph Daniels wrote of the meeting in his diary, the “subjection of the Negro, politically, and the separation of the Negro, socially, are paramount.” Wilson set back civil rights half a century.

Wilson also strongly opposed giving women the vote. Cox writes that led to “protests against the president.” In fall 1917, “successive waves of volunteers continued to carry banners in silence to the sidewalk in front of the White House. Each time, they were arrested, summarily convicted of ‘obstructing justice,’ and shipped off to serve ever-longer sentences at Occoquan and the District Jail.”

Both jails normally were segregated. But the white and Black suffragettes were put in the same cells, which “quickly backfired. It did not take long for the white newcomers to befriend their fellow inmates, and to learn from them.” The women were treated badly and their health declined until released.

Eventually, Congress and the states ignored Wilson and enacted the 19th Amendment. In 1922, out of office and his health rapidly declining, he said to Rep. Cordell Hull of the women then voting, “I shall be very much disappointed in them if they have forgotten that they are chiefly indebted to me for the suffrage.”

Wilson also weaponized the Secret Service, convincing “Democratic congressional leaders to appropriate $100 million (equivalent to $2.3 billion today) for the Secret Service, ‘to be expended at the direction of the President” – a slush fund. It “gained advance knowledge … on the suffrage protesters” and others.

“The light withdrawn” subtitle of Cox’s book comes from the poem “Ichabod” by John Greenleaf Whittier, a scathing attack on Daniel Webster for backing the Compromise of 1850 and its Fugitive Slave Act. Once considered among the greatest presidents, that now is Wilson’s fate.

John Seiler is on the SCNG Editorial Board.